Latinos are the largest minority group in the United States, with one in five children in the K-12 population coming from a Latino immigrant family and Latino children are the largest group of children living in poverty in the United States (Gilbert, Brown, & Mistry, 2017, p. 1202). Schools focusing on the health and wellness of students and their families can help foster success academically, physically and emotionally. Educators, communities and families working together towards this goal can benefit individuals, which then allows communities to thrive. Collaboration is the key to success for any common goal.

What Can Schools Do to Support Latino Students?

Increasing Wellbeing and Academics Through Breakfast in the Classroom

“Advocates argue that moving breakfast from the cafeteria to the classroom provides myriad benefits, including improved academic performance, attendance, and engagement, in addition to reducing hunger and food insecurity among disadvantaged children” (Corcoran et al., 2016, p. 510).

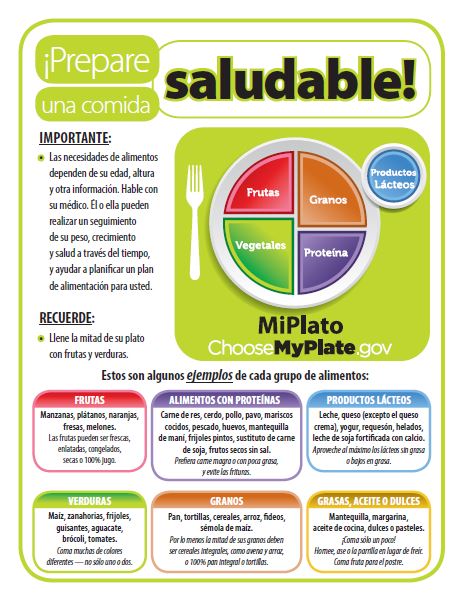

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), student participation in the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) School Breakfast Program (SBP) is associated with increased academic grades and standardized test scores, reduced absenteeism, and improved cognitive performance (CDC, 2018). Students need to eat healthy meals in order to concentrate in school and do well academically and behaviorally. “There is a critical need for culturally relevant interventions to address obesity among Latino children, who have a greater risk of obesity and diabetes than non-Hispanic white children” (Falbe, Cadiz,Tantoco, Thompson, & Madsen, 2015, p. 386). In order to increase participation in the SBP, a number of school districts have adopted Breakfast in the Classroom (BIC), a program that offers free breakfast to students in the classroom at the beginning of the school day, rather than serving it in the cafeteria. Taking the first 15 minutes of school to serve breakfast to students would be a positive way to start the day. Students could be in charge of picking up the food, serving and cleaning up.

Engaging Students and Families with School and Community Gardens

“School garden programs continue to grow across the country and receive national attention for the breadth of possible impacts from gardening and garden-based education” (Diaz, Warner, & Webb, 2018, p. 143). Recent studies have determined that students who participated in school garden projects demonstrated increased standardized test scores, applied concepts to real-world experiences, improved social skills, increased vegetable consumption and showed a heightened interest in nutrition education” (Duncan, Collins, Fuhrman, Knauft, & Berle, 2016, p. 175).

The school garden will give children opportunities to grow and harvest their own fruits and vegetables. During health classes, nutrition lesson would be implemented. Common core science standards could be intertwined with the school garden. Cross-curricular projects with math and language arts could be centered around the school garden. There are endless opportunities with a school garden. Students would be vital in cultivating the garden and learning in that space. Eventually, the garden would be used to help create meals for lunch as well as students being able to take home garden items and share with their families.

Building Community One Garden at a Time

Ted Talk on Building Community One Garden at a Time

School-Based Health Centers

School-Based Health Centers

Collaboration among the schools, health and community sector to improve each child’s learning and health can help close the achievement gap. School Based Health Centers (SBHC) are inside schools to provide services such as sports physicals, flu shots, eye exams, hearing exams, tests for strep throat, and check ups for diabetes and asthma. These centers make getting access to health care easier. The centers accept Medicaid, Child Health Insurance Plan (CHP) and are on a sliding scale based on family income. My district has SBHCs in each community and a key to these centers working is getting the word out about the services that they provide.